One Verb To Rule Them All

How one foreign language verb can profoundly affect your life

Pick one moment from this week that you usually do on autopilot. Not your most heroic moment, just something ordinary: the Monday staff meeting, that Slack ping you always answer too quickly, the way you handle the last ten minutes of your day. Hold that in your mind. We’re going to turn it into a tiny experiment you actually experience and learn from.

Some of you are looking for the tl;dr… and while I’d love to give you one, it is actually the antithesis of what you need for this exercise. So, a little background seems appropriate.

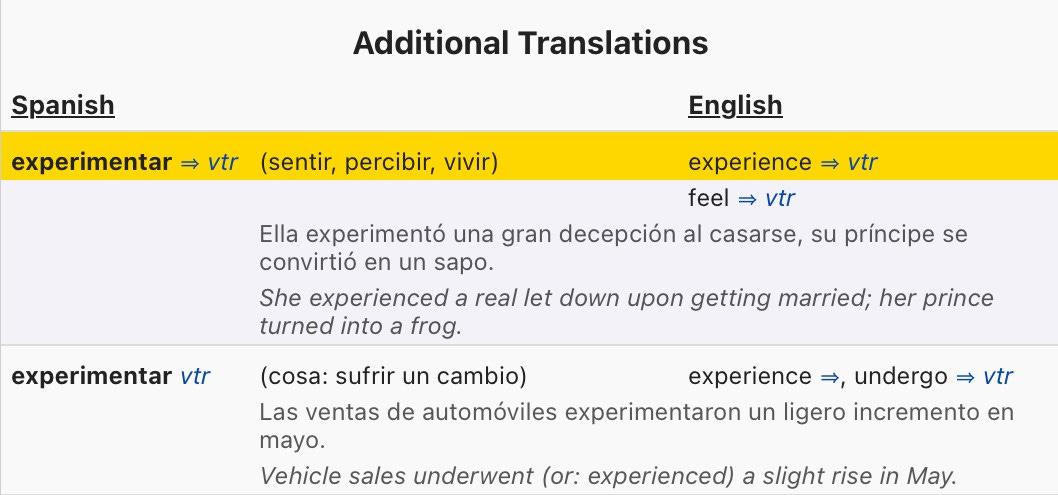

The whole idea of this article started while I was working on some Spanish grammar exercises. I came across the verb experimentar in a sentence about patients and their recovery. My English brain tried to translate it as experiment, and the result was wildly off: “The patients experimented major improvement.” That makes zero sense in English. A quick visit to WordReference.com showed me that experimentar carries two meanings: to experiment and to experience. One verb, two ideas. It incorporates both the deliberate test of an experiment, and the lived reality of an experience.

I engaged with a couple of Generative AI LLMs to summarize the etymology of both the single Spanish word and the two English words, I considered the implication of experiment and experience sharing the same dictionary space. This, it turns out, is exactly what I try to express to my clients from our first session. While Coaching involves a lot of conversations, it’s ultimately about taking action. Or really, about “trying things” based on the outcome of those conversations. In other words, designing an experiment to try. An experiment to experience something new, something that hopefully lies outside of your current comfort zone, so that you can experience that new thing and learn from it. The experiment you do on purpose; the experience you gain from living it. Put simply:

The experiment creates the experience. The experience leads to learning.

“Nice, David,” you say, “but while the etymology of Spanish words isn’t particularly interesting to me… and I don’t see how knowing it is going to profoundly affect my life.”

So let’s make this practical. Here’s a simplified loop based on what my clients and I do in (and between) sessions. You can run with it this week on that everyday situation you selected a minute ago, or select a different one.

The simple loop

Choose → Design → Perform (Experience) → Learn → Apply

Choose (90 seconds). Name one specific recurring moment where you want a different experience. Keep it small and real. “Tuesday 1:1 with Jordan,” “first Slack ping after lunch,” “the last ten minutes before I shut the laptop.” Now write a one-line script:

“In [situation], I’ll experiment with [behavior] so I can experience [state].”

Examples:

“In my 10 a.m. sync, I’ll experiment with speaking last so I can experience more curiosity than pressure.”

“When the next urgent Slack comes in, I’ll experiment with asking ‘What outcome do you want?’ so I can experience clarity instead of digital ping-pong.”

“At 5:20 p.m., I’ll experiment with writing three sentences about my day so I can experience closure instead of carryover.”

Design (5 minutes). Make the experiment tiny, visible, time-boxed, and safe-to-fail. Tiny means you can do it without special conditions. Visible means you’ll notice yourself doing it (or not doing it). Time-boxed means you know when it starts and ends. Safe-to-fail means you’ve decided what “messy” may look like and that you won’t treat “messy” as a character flaw. Add one guardrail:

If I slip into the old habit, I’ll pause, remind myself of my intent, and continue.

Perform (Experience). Now do it in the real world. This part is less glamorous than it sounds. You may feel a tug back to your default settings. That’s normal. While you’re in it, pay attention to both the outside and the inside: the words you say, the silence you allow, the look on someone’s face. Also notice your breathing, shoulders, jaw, and the story you’re telling yourself about what’s happening. You’re not grading yourself. You’re noticing.

Learn (5 minutes). Right after, jot three short bullets:

What happened?

What did I experience?

What did I learn?

If you’d like a quick snapshot, rate before vs. after on 1(low)–5(high) for Pressure, Clarity, and Energy. Not because there’s a perfect score, but because the numbers can help your future self see patterns.

Apply. Decide one specific way you’ll use that learning next time. Keep this crisp:

“Because I learned X, I will do Y the next time this situation appears.”

Note that “Y” might be different from your original intention; you can (and should) modify it based on what you learned. Note that if the situation you selected occurs regularly, such as closing your day, you might want to execute the same behavior for several days before making any modification. One time does not a pattern make. The culmination of several experiences will likely yield stronger learning.

That’s the loop. It’s not complicated, but it is intentionally designed. And yes, it’s different from crossing off an action item. Action items are binary: pass/fail. Experiments are about learning. When you aim at learning, you free yourself to try something honest enough to move the needle.

Two quick stories to ground this.

Cross-functional peer. A client wanted a better working relationship with a peer who reliably “gummed up the works” at critical meetings. We could have created a script for shutting down the peer and declared victory. Instead, we designed an experiment for their next 1:1: ask two genuine questions before proposing any fixes; allow 5 seconds of silence before talking. The intended experience wasn’t victory; it was curiosity over defensiveness. Afterward, my client wrote three lines: what happened, what they experienced, what they learned. The result? They noticed a softer tone and less pressure in their own body. And the overall conversation improved. They decided to repeat the same move at the project review, and to literally count to five before jumping in. That’s learning you can use.

Testing a nomadic season. Another client was drawn to a more nomadic life but worried about “not having a home base.” We built a ladder of experiments: one week nearby, three weeks in an extended-stay hotel, two months further away. Each rung created real experiences with food, mail, haircuts, healthcare, and focus. The surprises weren’t the romantic ones; they were the system ones: what broke first, what stayed frictionless. After each rung, they captured the learning and applied it before climbing to the next rung. By the time the two-month experiment began, they had several new systems in place, and a more accurate appreciation about what “home” means for them.

If you’re thinking, “This sounds like permission to try,” you’re right! When I managed teams, people could change almost anything with two constraints: (1) Explain what the current process does and what impact changing it might have. (2) We design an experiment together.

I never graded the experiment on success/failure. I valued the learning. That’s why people actually innovated. They didn’t have to “go rogue” to make something better. They needed permission and a design.

Coaching isn’t so different. Most people don’t need another scheme or app; they need one experiment worth experiencing, and then a way to apply the learning. If the outcome aligns with your hunch, great! That’s icing on the cake. If it doesn’t, great! You still get cake (sans icing) because you still had the experiences that gives you a better view of reality and a next step that isn’t guesswork.

If you’re not sure what to try, use the examples I mentioned above and describe below. Pick one or more experiments, experience living through them, and see what you learn.

Speak Last to Listen More. In your meetings, let two other people speak before you. Ask at least one clarifying question before offering your view.

Respond Differently. When the next urgent Slack or Teams or (insert system of choice) message arrives, reply first with: “What outcome do you want?” Then respond based on that outcome, not the anxiety the interruption caused.

End-of-Day Review. Close your day by writing three short lines: What happened? What did I experience? What did I learn? Tomorrow, begin with a single “Apply” line: What I’ll do with that learning.

You’ll notice none of these require a personality transplant, a life overhaul, or a week-long retreat without internet. They’re small by design. Small is how we learn in the presence of real life.

And please let me know about your experiences and learnings! I’m always gathering the experiences of others so I can continue to refine ideas like these. If you want help designing better experiments for how you lead, that’s work I love. Let’s chat!

P.S. A brief language footnote, because if you know me, you know I really can’t resist sharing (hat tip to Generative AI for this information).

Experiment and experience both trace back to the Latin experīrī—“to try, test, undergo.” Spanish experimentar still carries both senses; it lets you say, in one word, that you’re going to run a test and live through it.

English split the ideas into two words. In English, we borrowed twice at different times:

"Experience" came earlier (14th century) through Old French experience, keeping the meaning of living through something.

"Experiment" came later (14th-15th century) as a more technical, scientific term through Old French esperiment.

Great post! “Experimentar” reminds me that we all like to believe we are free thinkers, unencumbered. The reality is our view of reality has boundaries defined by how we choose to talk/listen and in what language.

In grad school when studying the nervous system and perception the prof talked about “the truth” and being “civilized.” In being civilized we train children what to block out and what to let through to be perceived. This is done PRIOR to getting to think about the experience. ‘Nuff said. Thanks for the post!